The adoption of new medical technologies - a focus on outcomes and value

Medical devices – is value-based healthcare a help or a hindrance?

Any innovative intervention in healthcare should demand us

to ask of ourselves the problem we are

trying to solve, the desired outcome for

this individual, and the associated

costs and ramifications for the wider healthcare system. Nowhere is this more

true than in the development and adoption of diagnostic, monitoring and

therapeutic medical devices.

An evidence-based path to adoption of novel devices which

may be of very high value to patients has been problematic, as highlighted by

the recent excellent article by Campbell et al, ‘Generating evidence for new

high-risk medical devices’. Additionally there are differences between the

type of data collection required and evidence needed to support HTA decision

making between diagnostic and therapeutic devices.

What we are seeking to do is achieve value for patients (in

terms of the outcomes that matter to them) and healthcare providers and

governments who are under pressure to balance resource allocation to meet

multiple needs of patients across the population they serve.

Therefore we want to adopt novel devices quickly when they

show a lot of promise but also subsequently ensure that they deliver on that

promise in the lives of real people. We can and should back up that decision

making with ongoing outcome data capture including patient-reported outcomes as

part of real world evidence generation. The push towards value-based healthcare

is helpful in this regard as it encourages the embedding of patient-reported

outcome data capture into direct care, thereby making it a more sustainable

endeavour with the ability to create more robust data sets. The implementation

of patient-reported outcome measurement should never be set up as a data

collection exercise alone. Patient -reported outcomes can enhance the

communication between patients and their clinical teams and therefore have a

range of uses in supporting shared decision making, acting as triggers for key

conversations and as a needs assessment, long before we have acquired larger

datasets for value analysis.

Much has already been said about the need for a new

relationship between industry and healthcare systems, particularly in considering

new contracting models based on patient outcomes. This should not be

misunderstood, as this new relationship with industry is not about driving the

medical industrial complex in isolation without taking account of the impact of

an intervention on the whole system of care for patients. We accept that

industry has to be profitable. However, to achieve maximum value for patients

we need to also ensure that we undertake two additional activities.

The first of these is of course to minimise unnecessary costs

by adopting the most cost effective product on the market. Careful attention to

outcomes is necessary in order to make this judgment.

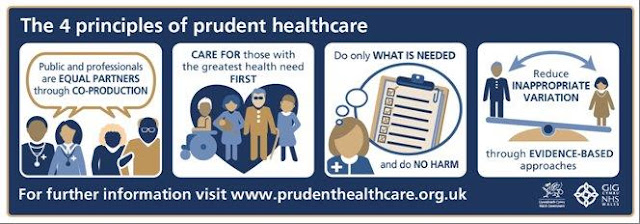

The second is to ensure optimal positioning of devices in

the patient pathway. Does evidence based medicine not achieve this? If we look

at any atlas of variation on device utilisation it would appear not. For

example, the use of implantable devices for patients with advanced heart

failure often correlates only with the proximity of the patient’s home to the tertiary

centre. Unwarranted variation, both over- and under-treatment exist and we must

tackle both. If we look at the definition of evidence-based medicine as

outlined by David Sackett, we may be able to guess at the answer why.

• ‘Evidence-based

practice is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best

evidence in making decisions about the care of the individual patient. It means

integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external

clinical evidence from systematic research.’

• ‘The

patient brings to the encounter his or her own personal preferences and unique

concerns, expectations, and values.’

Crucially, evidence-based guidelines tend to miss out the

second part about the patient’s context and the shared understanding of their

situation with their clinician. This in turn may subsequently influence choices

made about the appropriateness of an intervention for that individual including

whether to receive a medical device. This problem impacts on monitoring devices,

for example CGM in diabetes or telemetry in heart failure; and therapeutic

devices, for example implantable defibrillators or resynchronisation devices in

heart failure patients.

Condition-specific patent-reported outcome data are

essentially structured communications about symptoms and health status between

an individual and their clinician. It therefore provides information both about

need and about impact of an intervention on quality of life in a very specific

way. Unlike generic measures of quality of life such as the EQ5D, it is

generally harder to generate QALYs (quality adjusted life years), the

comparable measure of cost effectiveness usually employed by health economists

as part of the bases for a health technology assessment. However, I would argue

that these measures give us much more information about the impact of an

intervention.

If we can embed patient-reported outcome measures as a

useful activity in the direct care of patients, and find ways to use this data

including in the generation of QALYs from condition-specific tools, then we

will enhance our ability to assess the value of medical devices and their true

impact on the lives of patients.

Comments

Post a Comment