Tackling the backlog...or...meeting people's needs

As we emerge from the terrible throes of the pandemic, anxiety is growing about the large numbers of people waiting for services.The backlog of people waiting is enormous and compounded by the fact that we will face reduced capacity in the system for some time to come. I wrote about the challenges of delivering essential and life-preserving services during the pandemic in this previous article . Arguably the challenges of tackling the backlog, of meeting the needs of those waiting, are even greater and will require a collective and creative redesign of our systems.

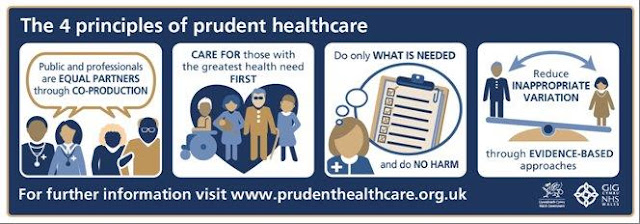

None of this is new of course. We have known for some time that our system of healthcare does not always entirely meet the needs of the population. Lack of funding is often highlighted as the reason for this and it is true that investment is needed in some areas, but fundamentally we are still operating in a system which was designed in a different context, a different culture of healthcare, a population with different needs, and far fewer interventions at our disposal to treat patients. To continue with the existing overall model of care we have neither the staff nor the buildings to accommodate the kind of activity needed to tackle the backlog or more accurately, to meet the needs of our patients and ensure good outcomes for all. Neither is this unique to the UK. Prior to the pandemic many initiatives around the world have sought to create cultural change in healthcare towards a more sustainable model, better experience and outcomes for patients, and to reduce burnout in healthcare professionals. Most notably in the UK Prudent healthcare in Wales, Realistic Medicine in Scotland and value-based healthcare attempt to refocus how we meet need.

So, returning to the backlog. What do we mean by backlog? People are waiting but they are waiting for different reasons and with varying degrees of urgency. People may have been referred to hospital outpatients because of diagnostic uncertainty, because primary care cannot access advice or tests another way, for uncontrolled symptoms, or to access a procedure. Similarly, large numbers of people remain on follow up waiting lists. Many of these are quite well and just need to remain in contact with their clinical team should problems arise or if monitoring is required.

Others are waiting for surgery or other hospital-based procedures. This requires a different approach. All patients needing surgery require a surgeon. Can we protect planned procedures from repeated cancellations caused by emergency pressures?

One of the approaches commonly used to standardise care and ensure that people see the right professional at the right time is the construction of pathways. Pathways are standardised evidence-based guidelines for stepwise management of a range of different symptoms and conditions. They are both an important educational tool and also have the potential to reduce unwarranted variation in care through either over- or under-intervention at any point in an individual's experience of illness. However, for many conditions pathways are insufficient because they do not take into account the nonlinear nature of chronic illness, fluctuating symptoms or the preferences and goals of the individual. They are undoubtedly more useful for some conditions than for others and they also occasionally create an unintended consequence of getting someone stuck in the system with no service able to meet their need.(for example if referral criteria are not met) Need is need. It doesn't go away and we have to meet it.

So how could we augment pathway design to improve outcomes and reduce healthcare utilisation. (And we must contain healthcare costs somehow, or we will start to see reduced investment in the very things that make us healthy, such as education, leisure, sport and the arts). An example of this is seen in the oft cited 'self-management' part of a pathway which is a catch all term for how a person manages their own symptoms such as pain, or monitors and manages a chronic condition such as diabetes or asthma. Self-management doesn't happen by accident. People need to be actively supported in this regard and frequently the approach to this is not sufficient to meet the need. Low cost high value investment into these simple interventions can hugely improve outcomes whilst also reducing onward healthcare utilisation. My colleague Kathrin Thomas lamented on Twitter that 'we are still focused on a model based on technocratic cures for single diseases rather than sophisticated community approaches for wellbeing and managing multimorbidity.' This does not mean at all that primary and secondary care should be at war and that we should not invest in specialist care. What it means is that if we don't attend to the way we currently support patients in the community we will continue to overwhelm specialists with multiple referrals and create frustration for our patients.

The other big generator of referrals is perceived clinical risk and usually that is about diagnostic uncertainty. Addressing that through improved communication between primary and secondary care and shared ownership of that risk is really key to reducing traditional referrals and much has already been done to support this approach.

Finally, alternative models of care require huge cultural change for all of us, whether giving or receiving care. If we are to 'tackle the backlog' and meet everyone's need, we must all accept the need to do this differently. We can borrow from the rest of the world or we can design our own, but now is the time.

Comments

Post a Comment