Shared understanding before decision making

Whilst messing about on social media this weekend I stumbled

across some conversations that gave me a bit of a jolt. Shared decision making,

that pillar of the consultation in healthcare, something I thought was an

unassailable pursuit, was under attack. Some even commented that it should be

ditched altogether. In favour of what I thought? A return to paternalism? Perish

the thought! I was incensed! I couldn’t stop thinking about this and wondering

why some of my medical colleagues around the world had turned against this

approach and were now describing it in a number of disparaging ways. Views

ranged from it being a rather pompous term where the rhetoric far outstrips the

reality to being something which is an assault on patient autonomy or in some

cases, an assault on physician autonomy. In some cases, surely, doctor knows

best?

Shared decision making has been described as ‘a process in

which both the patient and the physician contribute to the decision-making

process.’ Other related terms have been coined such as ‘no decision about me,

without me’.

I found myself nodding in agreement that good shared

decision making tends to be aspirational rather than a consistent reality. Some

of us try harder than others, but in spite of all our efforts we are really not

as good at involving people in decisions about their healthcare as we think we

are.

I wanted to think a little more deeply about why it is so

difficult, but first to tackle something with which I am not in agreement, and

that is the notion that shared decision making is somehow a bad thing and

should be ditched.

Using the Beauchamp and Childress’ old ethical framework as

a guide let’s look at the issue of autonomy.

Patient autonomy means that an individual must be able to make their own

decisions about their health without undue influence. It is the basis for

informed consent and also means that people can make what the practitioner may

regard as being unwise choices. It is entirely up to the individual. However,

this does not absolve the doctor of the duty to inform sensitively and

factually about the likely outcomes of different courses of action.

What about decisions made autonomously by the physician? These days this refers to the doctor making the decisions on behalf of the patient based on today’s

evidence-based guidelines. There are a few emergency situations where this is

entirely appropriate and sensible but in most cases is and should be seen as

paternalistic at best. No decision about me without me. However, some people may request that the practitioner makes a decision on their behalf. This carries even greater responsibility to explore the beliefs and wishes of the individual seeking help.

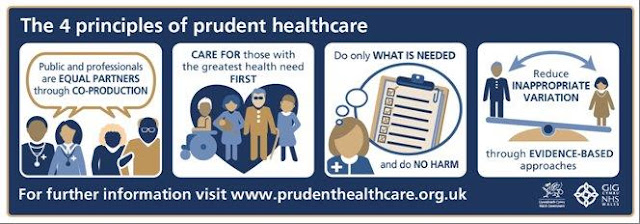

The ethical principle of autonomy does not exist in

isolation but must be considered in line with the other principles of

beneficence (promote what is good and in the best interests of the patient),

non-maleficence (do no harm) and justice (fairness, equity and respect for

rights and law). To achieve the best

outcome, both sides must share the knowledge that they have. The patient shares

their context, wishes and goals whilst the physician shares their medical

knowledge. Marrying the two sides together, we arrive at a course of action

bespoke for that individual’s circumstances.

That is the ideal scenario and the reality is often far from

this ideal. There are blind spots and knowledge gaps on both sides and usually a serious lack of time. The advice

we give as medical practitioners is riddled with ‘pseudo-certainty’ and we

often exercise our own clinical biases (often unconsciously) either over – or

under-playing the benefits and risks of this or that intervention. Surely then

in an ever more complex medical world shared decision making is more important

for us to master than ever. Together we can work towards what I think is better

described as the ‘shared understanding of medicine’ (courtesy of Professor

Richard Lehman) . Otherwise we reduce medicine to a merely technical discipline

of algorithms, orders and procedures which will neither help our patients nor

nourish us as individuals.

Comments

Post a Comment