Prudent health care principle two - a difficult one

The Prudent Healthcare Blogs

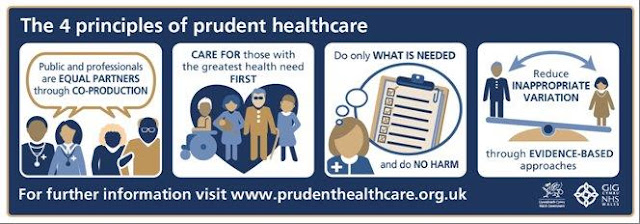

Principle Two

'Care for those with the greatest health need first'

At first glance the second principle seems obvious and straightforward to adopt. After all, who would deny that we should prioritise those in greatest need of care? However, as we consider this more carefully, we start to see that this is not at all as easy as it first appears. Do we really focus our resource and attention on those with greatest need? How do we define need?

When treatment is immediately life saving we can reassure ourselves that we are certainly prioritising those in greatest need and the NHS excels in this function, but what about when the situation is less acute? For example, in a healthcare system where resources will always be finite, how do we prioritise between the all of the needs of a population with, say, cancer and a population with neurodegenerative disease? In an ideal world of course we would be able to cater for the needs (and wants) of both populations - but life isn't like that and difficult decisions will always have to be made. Allocating resource between populations with disease A and disease B is ethically fraught and we must use the best available evidence in our decision making, considering always the opportunity cost and impact on other people.

This principle also steers us towards promoting equity in health and reducing heath inequalities.

Equity is defined as 'the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically'.

If we are to achieve this, a greater focus is therefore needed on certain demographic groups to achieve better health and this goes beyond healthcare itself, encompassing housing, education and other needs. It requires also a separate approach for those living with rare disease. Aristotle himself described the need for disproportionate provision in favour of those with greater need in his theory of distributive justice and yet the Inverse Care Law still exists in 2017, despite our best efforts to reverse it. We would do well to remember that those in greatest need often have the quietest voice and so in healthcare we must be strong advocates for the vulnerable if we are to reduce health inequalities.

The system is full of targets. These are well-intentioned but we must guard against unintended perverse consequences as, paradoxically, some targets can cause us to have the wrong focus.

Finally, there is always the deeply personal and emotive tension between individual and population need. When I am sitting in my surgery with a person in my care, I am thinking about their needs and how I can help address them. i am certainly not thinking about the population of my surgery as a whole, any more than if a member of my family was ill. This is the power of human interaction which we would never want to sacrifice. And yet, we all do have a responsibility for the wider population. In a national context, we must consider that an expensive new intervention with marginal benefit could displace invisible activity benefiting other individuals. Unfortunately cost effectiveness is not equivalent to affordability. Something and somebody always suffers as a result.

Not easy, is it?

I have come to the conclusion that this is the most challenging prudent healthcare principle of all and one that healthcare professionals cannot solve alone. What matters most in healthcare and how will we afford it? We need honesty and debate from politicos, journalists, professionals and public if we are to sustain our system. In spite of everything, it is the most equitable in the world.

Prudent care is important, and thank you for sharing this with us.

ReplyDelete